Monongahela Rye: The Rise, Fall, and Second Coming of the Historical Pennsylvania Rye Whiskey.

Since the mid-2000’s, there has been a growing popularity of cocktail culture within the United States, Western Europe and East Asia. Bars are increasingly making more mixed drinks and cocktails, each an attempt to be more interesting than the neat. Along with the rise in popularity of cocktails there is an increased popularity in American rye whiskey. To most, this spicy and daring type of whiskey seems relatively new, rapidly exploding from a few relatively unnoticed brands to an increasingly popular ingredient at trendy drinking establishments. But any aficionado or connoisseur would tell you that rye whiskey has always been there, even predating America’s oh-so-popular bourbon. It is simply making a well needed craft comeback.

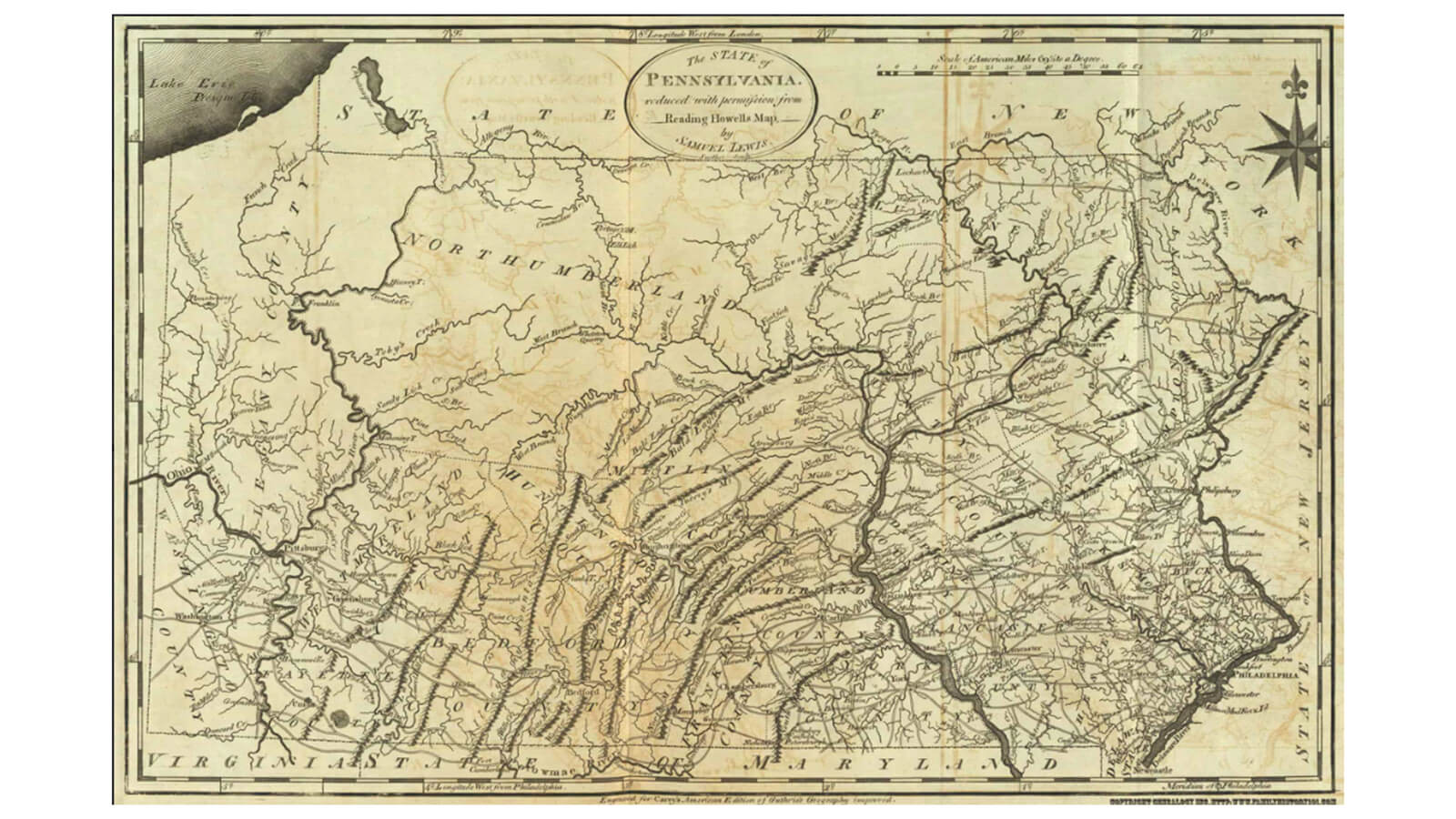

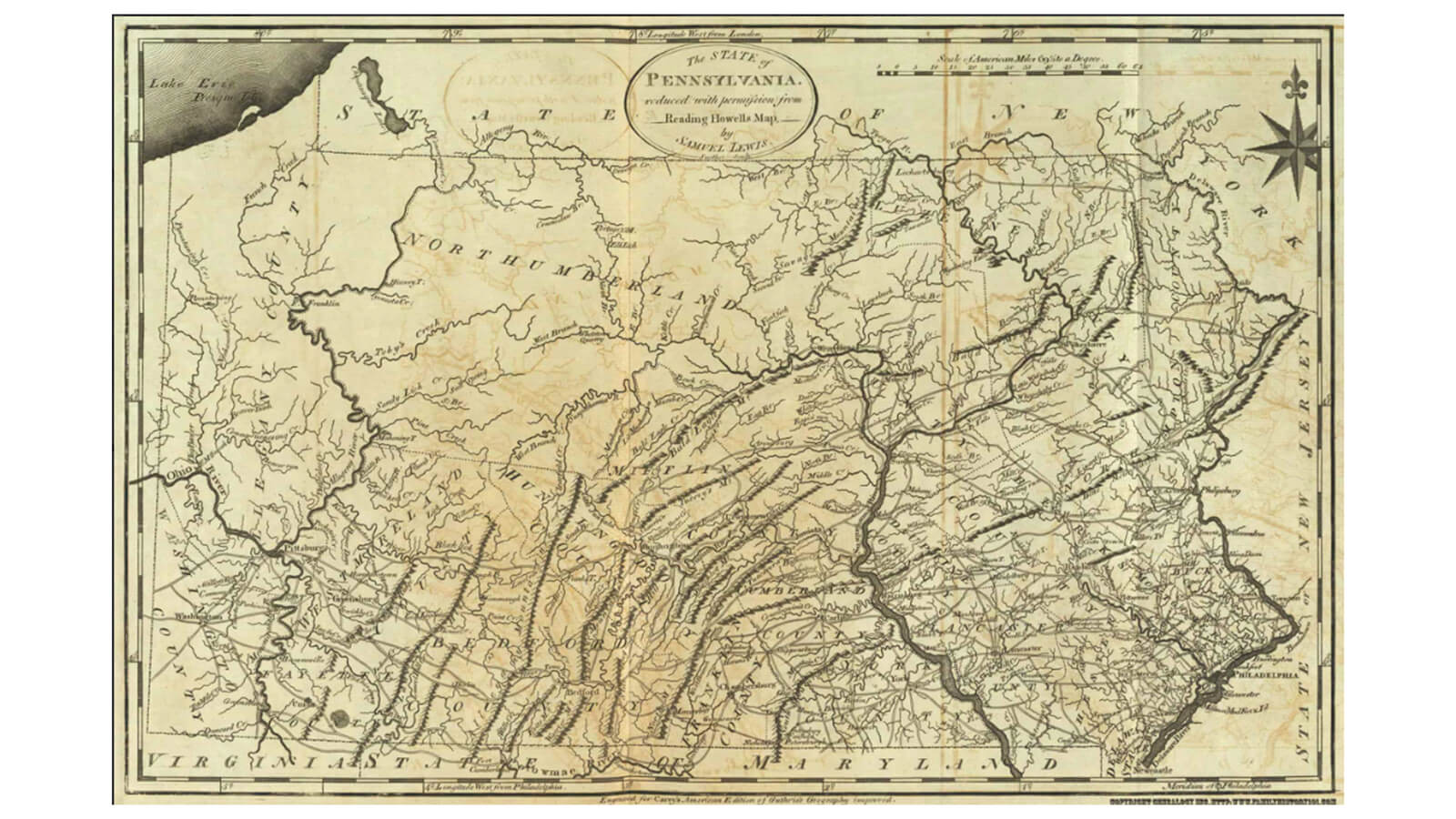

Rye whiskey dates back to the American colonial period, when German, Dutch and Swiss settlers started moving into the colony of Pennsylvania in the early to mid-18th century. Many were Mennonite farmers. Speaking to Herman Mihalich of Dad’s Hat Whiskey, he noted that rye was a familiar grain to these settlers, and it took well to the terroir of the central and western parts of the colony. Mihalich also pointed out that rye was wonderful in terms of agriculture; it was useful in the practices of crop rotation and using certain crops for nitrogen fixation. In an interview with historian Samuel Komlenic, he put it this way: “whiskey was a necessary part of the frontier. Settlers used it instead of currency, and it was considered a staple of everyday life”. The grain would quickly go bad if left untouched, so it would be made into whiskey. It took time to bring to market in the eastern area of the region, and was transported in wood barrels, giving it a better taste than what the farmers and distillers had in the western area of the region. There was even a rebellion in western Pennsylvania over a tax implemented on whiskey, which disproportionately impacted producers in the area due to their heavy reliance on whiskey. Unrest began in 1792 and culminated in October 1794 when President George Washington moved towards Pittsburgh with multiple state militias in order to stop the rebellion.

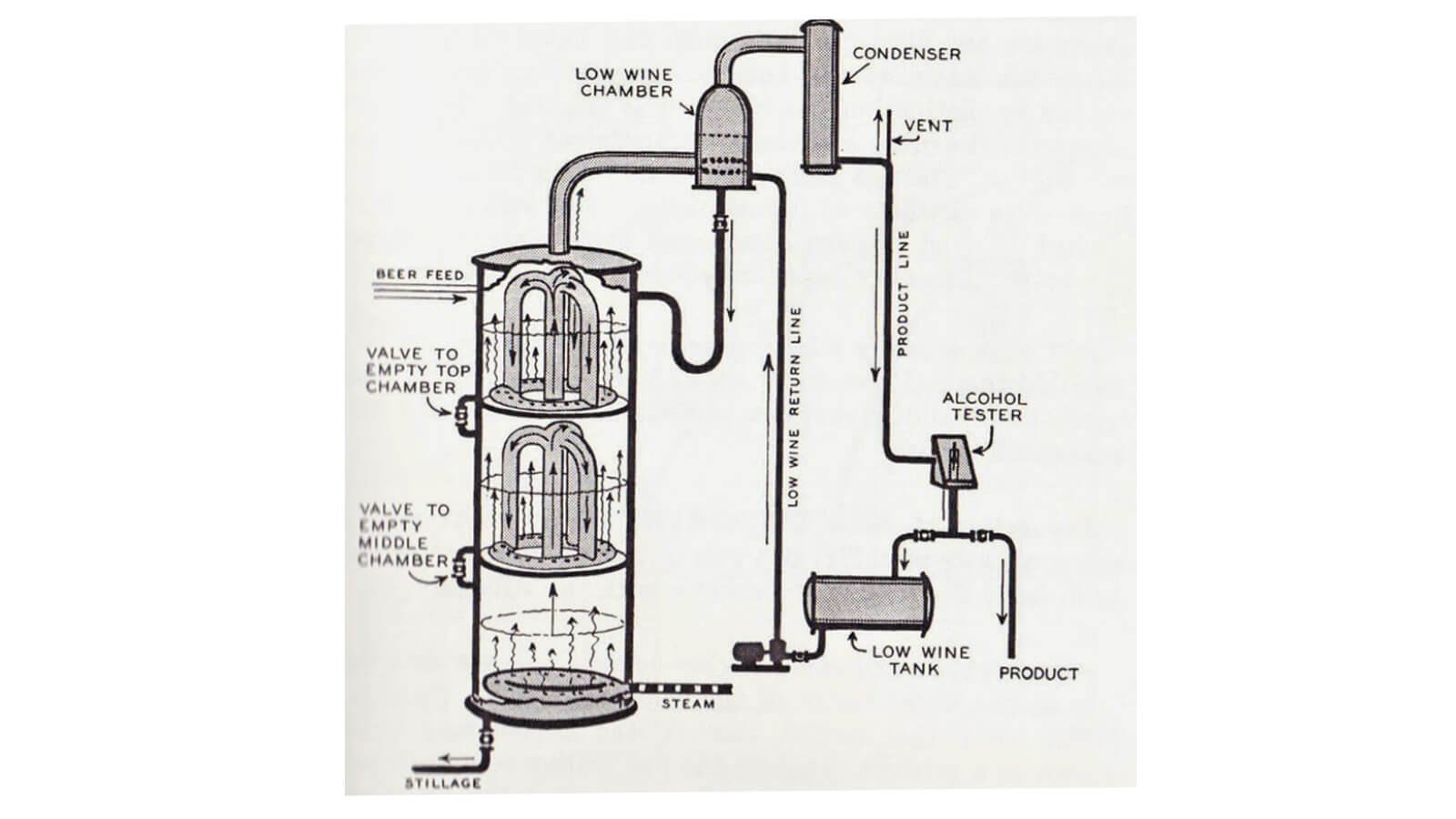

What exactly was Pennsylvania Rye whiskey, or what had been known as Monongahela whiskey? In my interview with him, Komlenic outlined the main features to make rye whiskey: first, the whiskey was mainly made using two grains in the mash bill – rye and barley- at the proportions of roughly 80 percent rye and 20 percent barley. This was often labelled as “pure rye”. According to Mihalich, malted barley was included to smooth the flavor and because it adds enzymes useful for fermentation that are not contained in rye. The other possible mash bill was called “all rye”, which is exactly what it sounds like: a mash bill of 100 percent rye grain, composed mostly of unmalted rye. The second feature was to use only sweet mash instead of sour mash. In the sour mash process, a small portion of the fermenting mash, or mixture of grains, yeast, and water prior to distillation, is taken from the last batch, then added to the next fermenting batch. The use of sour mash is a common feature of making bourbon, while Monongahela whiskey traditionally only uses sweet mash. This creates a slight variability between batches. The third defining feature was the usage of a unique still called the three chamber still. Komlenic explained that these were in relatively common use between the end of the American Civil War and just prior to Prohibition. In essence, a three chamber still consists of three pot stills stacked on top of each other. The design is an interesting fusion between the pot still and the more efficient column still. There are very few three chamber stills in existence today. The fourth and final feature was the aging process. Most American whiskey distilleries tend to use unheated wooden warehouses to store their barrels, which allows for both the building and the barrels to expand the contact with the changes in weather. This causes variations in the exchange between the barrel and the whiskey inside, depending on temperature, humidity, and season. Komlenic describes a very different aging process when dealing with Monongahela whiskey: Instead of unheated wooden buildings, he said that steam-heated buildings built with brick or other masonry were preferred. Distilleries often kept the buildings above 70 degrees Fahrenheit, or just over 21 degree Celsius, year-round. Combined with stone or brick buildings, consistent warmth allowed a greater interaction between whiskeys and barrels. The end result was a much deeper, richer, fuller bodied whiskey than what most modern rye whiskies taste like.

This style of whiskey seems to have vanished without a trace. Why? The most obvious reason is because of the damage done to America’s alcohol industry during the Prohibition era. A select few distilling companies were selected by the government to continue production for medicinal purposes, and consumers could get a prescription from a doctor to receive whiskey. Other distillers had to close their facilities, leading to financial ruin. Even after Prohibition, the entire industry had to restart, almost entirely without full barrels in store and in aging warehouses. It would take years to have product ready for market. Herman Mihalich points out that another factor hit rye whiskey much harder than bourbon. During Prohibition, there was big money to be made in running whiskey in from Canada, which was often illicitly labeled at speakeasies as “rye” when, in fact, it was simply blended whiskey. This blended Canadian whiskey was more affordable to make and more approachable for newer drinkers than the genuine Pennsylvania rye. This essentially stole the market away from the producers who were making Monongahela style rye, and those producers were never able to recover. However, according to Komlenic, “Prohibition was the nail in the coffin, but not the cause of the demise of rye”. Instead, he argues that 55 years prior to Prohibition the American Civil War was the root of its downfall. During the Civil War, troops from both the Union and Confederate States would have been likely exchanging goods, whiskies included. The sweeter, more dessert-like corn heavy bourbon that was much more popular in the American South found its way in the hands of Union men and became much more popular during and after the War. Soon, bourbon was outcompeting its spicy, savory neighbor. All these factors led to a very niche market with minimal production by the time Prohibition ended in 1933.

This style of whiskey seems to have vanished without a trace. Why? The most obvious reason is because of the damage done to America’s alcohol industry during the Prohibition era. A select few distilling companies were selected by the government to continue production for medicinal purposes, and consumers could get a prescription from a doctor to receive whiskey. Other distillers had to close their facilities, leading to financial ruin. Even after Prohibition, the entire industry had to restart, almost entirely without full barrels in store and in aging warehouses. It would take years to have product ready for market. Herman Mihalich points out that another factor hit rye whiskey much harder than bourbon. During Prohibition, there was big money to be made in running whiskey in from Canada, which was often illicitly labeled at speakeasies as “rye” when, in fact, it was simply blended whiskey. This blended Canadian whiskey was more affordable to make and more approachable for newer drinkers than the genuine Pennsylvania rye. This essentially stole the market away from the producers who were making Monongahela style rye, and those producers were never able to recover. However, according to Komlenic, “Prohibition was the nail in the coffin, but not the cause of the demise of rye”. Instead, he argues that 55 years prior to Prohibition the American Civil War was the root of its downfall. During the Civil War, troops from both the Union and Confederate States would have been likely exchanging goods, whiskies included. The sweeter, more dessert-like corn heavy bourbon that was much more popular in the American South found its way in the hands of Union men and became much more popular during and after the War. Soon, bourbon was outcompeting its spicy, savory neighbor. All these factors led to a very niche market with minimal production by the time Prohibition ended in 1933.

What does the future hold for Pennsylvania/Monongahela Rye? Both Mihalich and Komlenic notes that there is not any distillery that is currently producing whiskey that meets the four parameters above mentioned. Dad’s Hat seems to be very close in terms of mash bills. Mihalich says “Dad’s Hat tries to be very historically accurate. The mash bills are chosen for both taste and for history.” The Leopold Brothers Distillery, based in Denver, Colorado, seems to be one of the few distilleries using a three chamber still today. Yet, this company is producing a related style of whiskey, Maryland rye, which in the modern era tends to include some corn in the mash bill to create a more gentle and sweet whiskey. True Monongahela style rye whiskey had a much more pronounced, deeper, richer and full-bodied flavor profile. No whiskey producer within the United States seems to be using heated brick or stone buildings to store their barrels of whiskey. Komlenic said it like this: “Nobody who is making rye whiskey is making Monongahela rye because they don’t meet the first three parameters. No one to my knowledge is really trying to recreate it”. However, rye whiskey as a whole category seems to be making a major comeback as craft distilleries begin producing more, and consumers become more educated and curious. “More people want to learn about whiskey, especially rye and bourbon,” Mihalich says The recent boom in popularity could also be due in part to an increased popularity of cocktails and eased legislation in regard to opening new distilleries in several states, Pennsylvania and Maryland included.

I asked both Mr. Komlenic and Mr. Mihalich for cigar recommendations that they would pair with Monongahela Rye, or simply a fuller bodied rye in general. Mr. Komlenic immediately recommended the Diesel Unholy Cocktail in torpedo, a full-bodied cigar that uses tobacco from Nicaragua and the Dominican Republic, as well as Pennsylvania Broadleaf tobacco. Mr. Mihalich said he prefers to gravitate towards the milder to medium range of cigars in general and would reach towards something made by the La Gloria Cubana (not the brand made in Cuba, but the one made for the American market).

Do not miss any news and the highest rated spirits!